That there are mechanisms

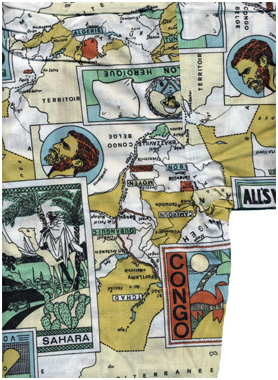

involved in framing cultural prejudices as objective scientific observation is an important historical insight having direct relevance to much of Ponger’s

work. Within the work group Made for Europe she engages with many aspects of colonialism and the sciences of anthropology and ethnology. That there are mechanisms

involved in framing cultural prejudices as objective scientific observation is an important historical insight having direct relevance to much of Ponger’s

work. Within the work group Made for Europe she engages with many aspects of colonialism and the sciences of anthropology and ethnology.

Anthropology and, up till relatively recently, ethnology, both purported to study human beings and their cultures from an “objective” standpoint.

That is a location we have had to accept does not exist because every criteria we can devise must of necessity originate within the  cultural system

that devises it. Put simply, any statement made about another culture which includes value judgements (and

almost all do) automatically includes our (Western) culture. In making such statements there is as much to be learned about our own culture as there

is about the culture being examined. How a question is framed and what it asks implicates the person responding in the value system of the questioner. cultural system

that devises it. Put simply, any statement made about another culture which includes value judgements (and

almost all do) automatically includes our (Western) culture. In making such statements there is as much to be learned about our own culture as there

is about the culture being examined. How a question is framed and what it asks implicates the person responding in the value system of the questioner. |

|

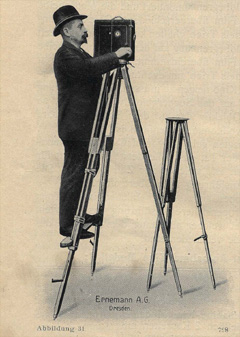

In

addition to that, the very fact of presuming to undertake studies of this nature implies a certain kind of relationship between those studying and those

being studied - the subjects and the objects. Even the simple physical presence of the ethnologist in a village somewhere in Africa or Asia has connotations

which illuminate this configuration of power. In the main, their safety was guaranteed - or at the very least made viable by - the existence of a colonial

army. In

addition to that, the very fact of presuming to undertake studies of this nature implies a certain kind of relationship between those studying and those

being studied - the subjects and the objects. Even the simple physical presence of the ethnologist in a village somewhere in Africa or Asia has connotations

which illuminate this configuration of power. In the main, their safety was guaranteed - or at the very least made viable by - the existence of a colonial

army.

Clifford sums up the situation: “All over the world ‘natives’ learned, the hard way, not to kill whites. The cost, often a punitive expedition

against your people, was too high. Most anthropologists, certainly in Malinowski’s time, came into their ‘field sites’ after some version of this violent

history. To be sure, a few daring researchers worked in unpacified areas, becoming, as they did so, part of the contact

and pacification process.” |