In

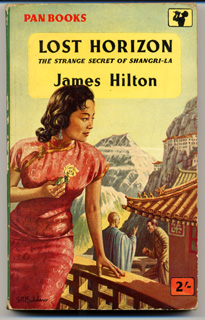

the many examples of Shangri-Las, the boundaries between imagination and reality, fact and fiction, are perfectly fluid. The need for idealized goals

is a legitimate and necessary part of being human, a prerequisite to generating the motivation to achieve them. But there is a point on the continuum

where desire and justifiable optimism begin to create the imaginary geographies of exaggerated yearnings. That is the sovereign territory of Shangri-La,

the image we create and the one we can be re-sold. Naturally enough the idea of a paradise, a Shangri-La, is not just restricted to Western cultures,

especially after other cultures have had contact with the West. The idea of a territorial embodiment of an easier life with more material possessions

crosses cultural divides: In

the many examples of Shangri-Las, the boundaries between imagination and reality, fact and fiction, are perfectly fluid. The need for idealized goals

is a legitimate and necessary part of being human, a prerequisite to generating the motivation to achieve them. But there is a point on the continuum

where desire and justifiable optimism begin to create the imaginary geographies of exaggerated yearnings. That is the sovereign territory of Shangri-La,

the image we create and the one we can be re-sold. Naturally enough the idea of a paradise, a Shangri-La, is not just restricted to Western cultures,

especially after other cultures have had contact with the West. The idea of a territorial embodiment of an easier life with more material possessions

crosses cultural divides:

“... it is about time to draw attention to the fact that in the Himalayas many people also dream of Shangri-La. |

|

But here

it is called something else: “America”, the promised land, the country that gives everyone a chance irrespective of caste or class. Above

all, of the Nepalese students who have been visiting the annual YMCA summer camps in the USA since 1984, only 20% have returned.” Kanak

Mani Dixit But here

it is called something else: “America”, the promised land, the country that gives everyone a chance irrespective of caste or class. Above

all, of the Nepalese students who have been visiting the annual YMCA summer camps in the USA since 1984, only 20% have returned.” Kanak

Mani Dixit

From numerous examples it can be seen how the idea of Shangri-La has shifted from a religiously-based, benign but hierarchical society

cut off from the rest of the world to a utopian vision of a me-centred, materialist paradise. Predictably all this illumination had to have a shadow

side. For the Christian church as well as the general public, it was to be found in Africa: The image of Africa as ‘the dark continent’ was a powerful

one to much of the British public in the second half of the nineteenth century. |